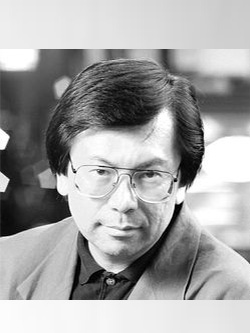

Find a Grave Corky Lee (1947-2021)

Find a Grave Corky Lee (1947-2021)

Full Name Young Kwok Corky Lee

Birth 5 Sep 1947

Queens, Queens County, New York, USA

Death 27 Jan 2021 (aged 73)

Queens, Queens County, New York, USA

Burial Unknown

Photojournalist

He was born Young Kwok Lee to parents who were immigrants from China to the US. He graduated from Queens College where he studied American history and started taking pictures in the early 1970s to document his work as a community organizer on the Lower East Side.

He became an activist with his camera striving to bring to light the underrepresented worlds of Chinese-Americans and others of Asian descent. It was his intent to capture moments of injustice toward those communities which meant photographing police brutality, protests and run-down housing, but also shop owners at work and young people break-dancing. In 1975, protests broke out in New York over police brutality in Chinatown.

During one, his camera captured an image of a bloodied man being led away by officers and it ran on the front page of The New York Post. For 45 years, he and his camera were omnipresent, and he became a sort of repository of Asian-American heritage, knowledge he shared in lectures and informal chats. He photographed Goldie Chu, an activist during feminism’s second wave at an Equal Rights Amendment rally in 1977.

He was in Detroit when protests erupted after two white men were not given jail time for the 1982 beating death of Vincent Chin, a Chinese-American whose killers apparently mistook him for Japanese and blamed him for the decline in auto jobs. He photographed Asian deliverymen picketing over wages at a Vietnamese restaurant in Greenwich Village and Indians demonstrating against anti-Hindu violence in Jersey City.

But not all his images were of strife and protest. He photographed Sonya Thomas, a Korean woman, after one of her several victories at the Coney Island hot dog eating contest. One of his favorite pictures was of Connie King, who was among the last Chinese-American residents of Locke, a rural outpost in California south of Sacramento that had once been home to immigrant workers. When white buyers took over the homes, they discarded the toilets because they didn’t want to sit where a Chinese person had sat. She repurposed them as planters, creating a sort of memorial that became something of a tourist draw. He was on Broadway in 1991 to photograph an opening-night picket of “Miss Saigon” protesting the show’s portrayals of Vietnamese people.

In 2002 he was a main organizer of a symbolic effort to correct the record regarding the railroad, gathering descendants of the railroad workers and other supporters at Golden Spike National Historical Park in Utah to recreate the image, this time with Asian-American faces. He took similar pictures in subsequent years. He did not confine himself to Chinese-American subjects and issues. One of his better-known photographs, taken in Central Park days after the terrorist attacks of 2001, captured a Sikh candlelight vigil intended to call attention to attacks against Sikhs, whom some people conflated with the terrorists.

The central figure in the picture is wrapped in an American flag. Once he became established, his work was frequently assembled for museum and gallery shows, including one at the Museum of Chinese in the Americas in New York in 2001.