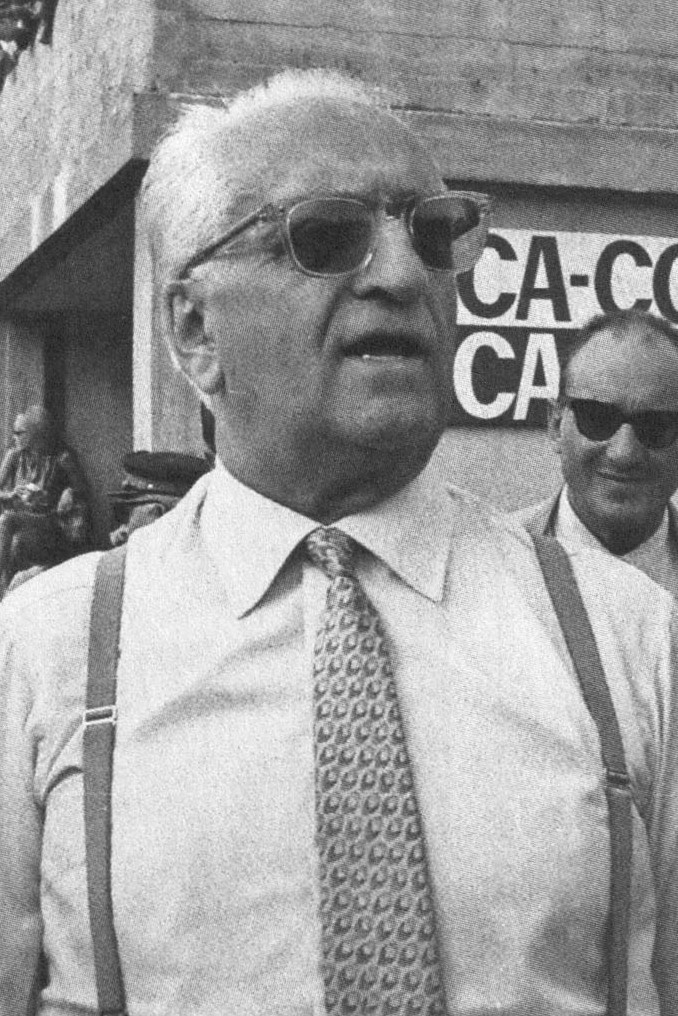

Enzo Ferrari (1898-1988) Italian Race Car Driver and Entrepreneur

Enzo Ferrari (1898-1988) Italian Race Car Driver and Entrepreneur dies at 79, Find a Grave Enzo Ferrari find a grave, Enzo Ferrari grave, Enzo Ferrari Death and burial details.

Enzo Ferrari was an Italian motor racing driver and entrepreneur, the founder of the Scuderia Ferrari Grand Prix motor racing team, and subsequently of the Ferrari automobile marque. Under his leadership, Scuderia Ferrari won 9 Drivers’ World Championships and 8 Constructors’ World Championships in Formula 1 during his lifetime.

Enzo Ferrari

| Full Name | Enzo Anselmo Giuseppe Maria Ferrari |

|---|---|

| Birth | 18 February 1898, Modena, Italy |

| Death | 14 August 1988 (age 90 years), Modena, Italy |

| Spouse | Laura Dominica Garello (Married 1923 and died 1978) |

| Children | Piero Ferrari, Alfredo Ferrari |

| Occupations |

|

| Known for | Founding Ferrari and Scuderia Ferrari |

| Partner | Lina Lardi |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Burial | Cimitero di San Cataldo, Modena, Provincia di Modena, Emilia-Romagna, Italy |

He was widely known as il Commendatore or il Drake, a nickname given by British opponents in reference to the English privateer Francis Drake, due to Ferrari’s demonstrated ability and determination in achieving significant sports results with his small company. In his final years, he was often referred to as l’Ingegnere (“the Engineer”), il Grande Vecchio (“the Grand Old Man”), il Cavaliere (“the Knight”), il Mago (“the Wizard”), and il Patriarca (“the Patriarch”).

Enzo Ferrari Biography, Family, Life, Age and Death

Enzo Ferrari was born on 18 February 1898 in Modena, Italy, although his birth certificate states 20 February. His parents were Alfredo Ferrari and Adalgisa Bisbini; he had an older brother Alfredo Junior (Dino). The family lived in via Paolo Ferrari n°85, next to the mechanical workshop founded by Alfredo, who worked for the nearby railways. This site is now the Enzo Ferrari Museum.

Alfredo Senior was the son of a grocer from Carpi and began a workshop fabricating metal parts at the family home. Enzo grew up with little formal education. Unlike his brother, he preferred working in his father’s workshop and participated in the construction of the canopy at the Giulianova station in 1914.

He had ambitions of becoming an operetta tenor, sports journalist, or racing driver. When he was 10, he witnessed Felice Nazzaro’s win at the 1908 Circuito di Bologna, an event which inspired him to become a racing driver. During World War I, he served in the 3rd Mountain Artillery Regiment of the Italian Army. His father Alfredo and his older brother Alfredo Jr. died in 1916 as a result of a widespread Italian flu outbreak. Ferrari became seriously sick himself during the 1918 flu pandemic and was consequently discharged from the Italian service.

Racing career

“Second place is the first loser.” (Original: “Il secondo è il primo dei perdenti”.)

After the collapse of his family’s carpentry business, Ferrari searched for a job in the car industry. He unsuccessfully volunteered his services to Fiat in Turin, eventually settling for a job as test driver for CMN (Costruzioni Meccaniche Nazionali), a car manufacturer in Milan that rebuilt used truck bodies into small passenger cars.

He was later promoted to race car driver and made his competitive debut in the 1919 Parma-Poggio di Berceto hillclimb race, where he finished fourth in the three-litre category at the wheel of a 2.3-litre 4-cylinder C.M.N. 15/20. On 23 November of the same year, he took part in the Targa Florio but had to retire after his car’s fuel tank developed a leak. Due to the large number of retirements, he finished 9th.

In 1920, Ferrari joined the racing department of Alfa Romeo as a driver. Ferrari won his first Grand Prix in 1923 in Ravenna on the Savio Circuit. 1924 was his best season, with three wins, including Ravenna, Polesine, and the Coppa Acerbo in Pescara. Deeply shocked by the death of Ugo Sivocci in 1923 and Antonio Ascari in 1925, Ferrari, by his admission, continued to race half-heartedly. At the same time, he developed a taste for the organizational aspects of Grand Prix racing. Following the birth of his son Alfredo (Dino) in 1932, Ferrari decided to retire and form a team of superstar drivers, including Giuseppe Campari and Tazio Nuvolari. This team was called Scuderia Ferrari (founded by Enzo in 1929) and acted as a racing division for Alfa Romeo. The team was very successful, thanks to excellent cars like the Alfa Romeo P3 and to the talented drivers, like Nuvolari. Ferrari retired from competitive driving having participated in 41 Grands Prix with a record of 11 wins.

During this period, the prancing horse emblem appeared on his team’s cars. The emblem had been created and sported by Italian fighter plane pilot Francesco Baracca. During World War I, Baracca’s mother gave her son a necklace with the prancing horse on it before takeoff. Baracca was shot down and killed by an Austrian aeroplane in 1918. In memory of his death, Ferrari used the prancing horse to create the emblem that would become the world-famous Ferrari shield. Initially displayed on Ferrari’s Alfa Romeo racing car, the shield was first seen on a factory Ferrari in 1947.

Building Ferrari

Alfa Romeo agreed to partner with Ferrari’s racing team until 1933, when financial constraints forced them to withdraw their support a decision subsequently retracted thanks to the intervention of Pirelli. Despite the quality of the Scuderia drivers, the team struggled to compete with Auto Union and Mercedes. Although the German manufacturers dominated the era, Ferrari’s team achieved a notable victory in 1935 when Tazio Nuvolari beat Rudolf Caracciola and Bernd Rosemeyer on their home turf at the German Grand Prix.

In 1937, Scuderia Ferrari was dissolved, and Ferrari returned to Alfa’s racing team, named “Alfa Corse”. Alfa Romeo decided to regain full control of its racing division, retaining Ferrari as Sporting Director. After a disagreement with Alfa’s managing director Ugo Gobbato, Ferrari left in 1939 and founded Auto-Avio Costruzioni, a company supplying parts to other racing teams. Although a contract clause restricted him from racing or designing cars for four years, Ferrari managed to manufacture two cars for the 1940 Mille Miglia, which were driven by Alberto Ascari and Lotario Rangoni.

With the outbreak of World War II, Ferrari’s factory was forced to undertake war production for Mussolini’s fascist government. Following Allied bombing of the factory, Ferrari relocated from Modena to Maranello. At the end of the war, Ferrari decided to start making cars bearing his name and founded Ferrari S.p.A. in 1947.

Enzo decided to battle the dominating Alfa Romeos and race with his own team. The team’s open-wheel debut took place in Turin in 1948, and the first win came later in the year in Lago di Garda. The first major victory came at the 1949 24 Hours of Le Mans, with a Ferrari 166 MM driven by Luigi Chinetti and Peter Mitchell-Thomson, Baron Selsdon of Scotland. In 1950, Ferrari enrolled in the newly established Drivers’ World Championship and is the only team to remain continuously present since its introduction. Ferrari won his first world championship Grand Prix with José Froilán González at Silverstone in 1951. Apocryphally, Enzo cried like a baby when his team finally defeated the mighty Alfetta 159. The first championship came in 1952 with Alberto Ascari, a feat that was repeated the following year. In 1953, Ferrari made his only attempt at the Indianapolis 500, but the car driven by Ascari crashed on lap 41 of the race.

To finance his racing endeavors in Formula One as well as in other events such as the Mille Miglia and Le Mans, the company started selling sports cars.

Ferrari’s decision to continue racing in the Mille Miglia brought the company new victories and greatly increased public recognition. However, increasing speeds, poor roads, and nonexistent crowd protection eventually spelled disaster for both the race and Ferrari. During the 1957 Mille Miglia, near the town of Guidizzolo, a 4.0-litre Ferrari 335 S driven by Alfonso de Portago was traveling at 250 km/h (160 mph) when it blew a tire and crashed into the roadside crowd, killing de Portago, his co-driver, and nine spectators, five of whom were children. In response, Enzo Ferrari and Englebert, the tire manufacturer, were charged with manslaughter in a lengthy criminal prosecution that was finally dismissed in 1961.

Deeply unsatisfied with the way motorsports were covered in the Italian press, in 1961 Ferrari supported Bologna-based publisher Luciano Conti’s decision to start a new publication, Autosprint. Ferrari himself regularly contributed to the magazine for a few years.

Many of Ferrari’s greatest victories came at Le Mans (nine victories, including six in a row from 1960 to 1965) and in Formula One during the 1950s and 1960s, with the successes of Juan Manuel Fangio (1956), Mike Hawthorn (1958), and Phil Hill (1961).

The Great Walkout

Enzo Ferrari’s strong personality and controversial management style became notorious in 1962. Following a rather weak title defense of Phil Hill’s 1961 world title, sales manager Girolamo Gardini, together with manager Romolo Tavoni, chief engineer Carlo Chiti, sports car development chief Giotto Bizzarrini, and other key figures in the company, left Ferrari to found the rival car manufacturer and racing team Automobili Turismo e Sport (ATS). Based in Bologna and financially supported by Count Giovanni Volpi, ATS managed to lure away Phil Hill and Giancarlo Baghetti from Ferrari, who responded by promoting junior engineers like Mauro Forghieri, Sergio Scaglietti, and Giampaolo Dallara, and hiring Ludovico Scarfiotti, Lorenzo Bandini, Willy Mairesse, and John Surtees to drive his Formula One cars.

The “great walkout” came at an especially difficult time for Ferrari. At the urging of Chiti, the company was developing a new 250-based model. Even if the car was finished, it was unclear if it could be raced successfully. Ferrari’s shakeup proved to be successful. The mid-engined Dino racers laid the foundation for Forghieri’s dominant 250-powered 250 P. John Surtees won the world title in 1964 following a tense battle with Jim Clark and Graham Hill. The Dino road cars sold well, and other models like the 275 and Daytona were on the way. Conversely, ATS, following a troubled Formula One 1963 campaign, with both cars retiring four times in five races, folded at the end of the year.

In 1998, Tavoni declared in an interview that he and the remaining Ferrari senior figures did not leave on their initiative but were ousted following a disagreement with Ferrari over the role of his wife in the company. He said: “Our mistake was to go to a lawyer and write him a letter instead of openly discussing the issue with him. We knew that his wife wasn’t well. We should have been able to deal with it in a different way. When he called the meeting to fire us, he had already nominated our successors.”

Merging with Fiat

By the end of the 1960s, increasing financial difficulties and the challenges of racing in many categories, along with meeting new safety and clean air emissions requirements for road car production and development, led Ferrari to start looking for a business partner.

In 1969, Ferrari sold 50% of his company to Fiat S.p.A., with the caveat that he would remain 100% in control of the racing activities and that Fiat would pay a sizable subsidy until his death for use by his Maranello and Modena production plants. Ferrari had previously offered Ford the opportunity to buy the firm in 1963 for US$18 million (equivalent to $179,139,130 in 2023 dollars), but late in negotiations, Ferrari withdrew once he realized that Ford would not agree to grant him independent control of the company racing department. Ferrari became a joint-stock company, and Fiat took a small share in 1965. In 1969, Fiat increased their holding to 50% of the company. In 1988, Fiat’s holding rose to 90%.

Following the agreement with Fiat, Ferrari stepped down as managing director of the road car division in 1971. In 1974, Ferrari appointed Luca Cordero di Montezemolo as Sporting Director/Formula One Team manager. Montezemolo eventually assumed the presidency of Ferrari in 1992, a post he held until September 2014. Clay Regazzoni was runner-up in 1974, while Niki Lauda won the championship in 1975 and 1977. In 1977, Ferrari was criticized in the press for replacing World Champion Lauda with newcomer Gilles Villeneuve. Ferrari claimed that Villeneuve’s aggressive driving style reminded him of Tazio Nuvolari. These feelings were reinforced after the 1979 French Grand Prix when Villeneuve finished second after an intense battle with René Arnoux. According to technical director Mauro Forghieri, “When we returned to Maranello, Ferrari was ecstatic. I have never seen him so happy for a second place.”

The Modena Autodrome

In the early 1970s, Ferrari, aided by fellow Modena constructors Maserati and Automobili Stanguellini, demanded that the Modena Town Council and Automobile Club d’Italia upgrade the Modena Autodrome, arguing that the race track was obsolete and inadequate for testing modern racing cars. The proposal was initially discussed with interest but eventually stalled due to a lack of political will. Ferrari then proceeded to buy the land adjacent to his factory and build the Fiorano Circuit, a 3 km track still in use to test Ferrari racing and road cars.

Final years

After Jody Scheckter won the title in 1979, the team experienced a disastrous 1980 campaign. In 1981, Ferrari attempted to revive his team’s fortunes by switching to turbo engines. In 1982, the second turbo-powered Ferrari, the 126C2, showed great promise. However, driver Gilles Villeneuve was killed in an accident during the last session of free practice for the Belgian Grand Prix in Zolder in May. In August, at Hockenheim, teammate Didier Pironi had his career cut short in a violent end-over-end flip on the misty back straight after hitting the Renault F1 driven by Alain Prost. Pironi was leading the driver’s championship at the time; he would lose the lead and the championship by five points as he sat out the remaining five races. The Scuderia went on to win the Constructors’ Championship at the end of the season and in 1983, with driver René Arnoux in contention for the championship until the very last race. Michele Alboreto finished second in 1985, but the team would not see championship glory again before Ferrari’s death in 1988. The final race win Ferrari saw before his death was when Gerhard Berger and Alboreto scored a 1–2 finish at the final round of the 1987 season in Australia.

Read Also: Trending Now and Join TELEGRAM

Auto racing and management controversies

Ferrari’s management style was autocratic, and he was known to pit drivers against each other in the hope of improving their performance. Some critics believe that Ferrari deliberately increased psychological pressure on his drivers, encouraging intra-team rivalries and fostering an atmosphere of intense competition for the position of number one driver. “He thought that psychological pressure would produce better results for the drivers,” said Ferrari team driver Tony Brooks. “He would expect a driver to go beyond reasonable limits… You can drive to the maximum of your ability, but once you start psyching yourself up to do things that you don’t feel are within your ability, it gets stupid. There was enough danger at that time without going over the limit.” According to Mario Andretti, “[Ferrari] just demanded results. But he was a guy that also understood when the cars had shortcomings. He was one who could always appreciate the effort that a driver made, when you were just busting your butt, flat out, flinging the car, and all that. He knew and saw that. He was all-in. Had no other interest in life outside of motor racing and all of the intricacies of it. Somewhat misunderstood in many ways because he was so demanding, so tough on everyone, but at the end of the day, he was correct. Always correct. And that’s why you had the respect that you had for him.”

Between 1955 and 1971, eight Ferrari drivers were killed driving Ferrari racing cars: Alberto Ascari, Eugenio Castellotti, Alfonso de Portago, Luigi Musso, Peter Collins, Wolfgang von Trips, Lorenzo Bandini, and Ignazio Giunti. Although such a high death toll was not unusual in motor racing in those days, the Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano described Ferrari as being like the god Saturn, who consumed his own sons. In Ferrari’s defense, contemporary F1 race car driver Stirling Moss commented: “I can’t think of a single occasion where a (Ferrari) driver’s life was taken because of mechanical failure.”

In public, Ferrari was careful to acknowledge the drivers who risked their lives for his team, insisting that praise should be shared equally between car and driver for any race won. However, his longtime friend and company accountant, Carlo Benzi, related that privately Ferrari would say that “the car was the reason for any success.”

Following the deaths of Giuseppe Campari in 1933 and Alberto Ascari in 1955, both of whom he had a strong personal relationship with, he chose not to get too close to his drivers out of fear of emotionally hurting himself. Later in life, he relented and grew very close to Clay Regazzoni and especially Gilles Villeneuve.

Enzo Ferrari Personal life

Enzo Ferrari lived a reserved life and rarely granted interviews. He seldom left Modena and Maranello and never went to any Grands Prix outside of Italy after the 1950s. He was usually seen at the Grands Prix at Monza, near Milan, and Imola, not far from the Ferrari factory, where the circuit was named after the late Dino. His last known trip abroad was in 1982, when he went to Paris to broker a compromise between the warring FISA and FOCA parties. He never flew in an airplane and never set foot in a lift.

Ferrari met his future wife, Laura Domenica Garello (c. 1900–1978), in Turin. They lived together for two years and married on 28 April 1923. According to Brock Yates’ 1991 book Enzo Ferrari: The Man and the Machine, Ferrari married to maintain appearances for the sake of his career, as divorce was frowned upon in predominantly Catholic Italy, and sought sexual conquests not so much for pleasure but for the gratification of his ego. According to Yates, Ferrari once remarked to racing manager Romolo Tavoni that “a man should always have two wives,” and at one point in 1961, when he was dating three women simultaneously, he wrote, “I am convinced that when a man tells a woman he loves her, he only means that he desires her and that the only perfect love in this world is that of a father for his son,” a comment that came several years after the death of his first son.

Ferrari and Laura’s one son, Alfredo “Dino,” who was born in 1932 and groomed as Enzo’s successor, suffered from ill-health and died from muscular dystrophy in 1956. According to Time magazine, Ferrari and Laura’s love for their son is what kept them together. Although Dino never raced, his father provided him with a fleet of cars that he raced for pleasure. He also designed engine parts while bedridden. Ferrari and Laura remained married until her death in 1978. John Nikas, writer and expert on the history of cars who founded the British Sports Car Hall of Fame, said of Ferrari, “His real loves in life were racing and Dino.”

Enzo had a second son, Piero, with his mistress Lina Lardi in 1945. As divorce was illegal in Italy until 1970, Piero could only be recognized as Enzo’s son after Laura’s death in 1978. Piero Lardi’s existence was kept a secret known only to a few of his father’s confidantes. According to Yates, “There is no question that at some point in the late 1950s, Laura Ferrari discovered her husband’s second life,” and openly derided him as a “bastard” when she saw him in a factory. After Laura’s death, Ferrari adopted Piero, who took the name Piero Lardi Ferrari. As of 2023, he is vice chairman of the company and owns a 10% share of it. Piero told the Los Angeles Times that Michael Mann’s 2023 biographical film Ferrari was accurate, in particular in its depiction of his father’s drive, saying, “My father was a person who was always looking ahead, moving forward, never going back.”

Ferrari was made a Cavaliere del Lavoro in 1952, to add to his honors of Cavaliere and Commendatore in the 1920s. He also received several honorary degrees, including the Hammarskjöld Prize in 1962, the Columbus Prize in 1965, and the De Gasperi Award in 1987. He was posthumously inducted into the International Motorsports Hall of Fame (1994) and the Automotive Hall of Fame (2000).

Enzo Ferrari Death

Ferrari died on 14 August 1988 in Maranello at the age of 90, of leukemia. Because he was a private person, and because he feared popular protests due to the fact that Ferrari’s team had been beaten by McLaren in every race of the 1988 season so far, Enzo expressed the wish for his death to be reported in the media only on 16 August, the day after his burial (witnessed only by his family) on 15 August. He witnessed the launch of the Ferrari F40 shortly before his death, which was dedicated as a symbol of his achievements. In 2002 Ferrari began production of the Ferrari Enzo, named after its founder.

The Italian Grand Prix was held just weeks after Ferrari’s death, and the result was a 1–2 finish for Ferrari, with the Austrian Gerhard Berger leading home Italian and Milan native Michele Alboreto; it was the only race that McLaren did not win that season. Since Ferrari’s death, the Scuderia Ferrari team has remained successful. The team won the Constructors’ Championship every year from 1999 to 2004, and in both 2007 and 2008. Michael Schumacher won the World Drivers’ Championship with Scuderia Ferrari every year from 2000 to 2004, and Kimi Räikkönen won the title with the team in 2007.

Find a Grave Enzo Ferrari

Cimitero di San Cataldo Modena, Provincia di Modena, Emilia-Romagna, Italy

Enzo Ferrari Cause of Death

No cause of death was given, though he was known to be suffering from kidney disease.

Enzo Ferrari: Frequently Asked Questions

1. Who was Enzo Ferrari? Enzo Ferrari was an Italian entrepreneur and founder of Ferrari, one of the most famous and successful sports car manufacturers in the world. He was born on February 20, 1898, in Modena, Italy, and passed away on August 14, 1988.

2. What was Enzo Ferrari’s background before starting Ferrari? Before starting Ferrari, Enzo Ferrari was a race car driver. He began his racing career in the 1920s with Alfa Romeo and gained recognition for his driving skills. In the early 1930s, he transitioned to managing racing teams and eventually started his own automotive company.

3. When was Ferrari founded? Ferrari was founded on September 20, 1939, as Auto Avio Costruzioni. The company produced its first car, the 125 S, in 1947, which marked the official birth of the Ferrari brand as we know it today.

4. What was Enzo Ferrari’s role in the company? Enzo Ferrari was the founder and long-time head of the Ferrari company. He was deeply involved in the design and development of Ferrari cars and was known for his hands-on approach to both engineering and racing.

5. Why is Ferrari so famous? Ferrari is famous for its high-performance sports cars, luxury vehicles, and significant success in motorsport. The brand is synonymous with speed, style, and engineering excellence. Ferrari’s success in Formula 1 racing, where it has been a dominant force for decades, also contributes to its global reputation.

6. What were some of Enzo Ferrari’s notable achievements in racing? Under Enzo Ferrari’s leadership, Ferrari achieved numerous successes in racing, including multiple Formula 1 World Championships and victories in prestigious endurance races such as the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Ferrari’s racing prowess played a crucial role in building the brand’s reputation.

7. Did Enzo Ferrari ever retire? Enzo Ferrari did retire from his role as a day-to-day manager of the company in the early 1980s, but he remained a key figure and an influential presence in the company until his death in 1988.

8. What was Enzo Ferrari’s philosophy on car design? Enzo Ferrari was known for his philosophy of combining beauty with performance. He believed that a sports car should be both a work of art and a high-performance machine. Ferrari cars are designed to deliver exceptional driving experiences while also reflecting elegance and style.

9. How did Enzo Ferrari influence the automotive industry? Enzo Ferrari’s influence on the automotive industry is significant. He set high standards for performance, design, and innovation in sports cars. Ferrari’s success on the racetrack helped push the boundaries of automotive engineering and inspired countless other manufacturers to strive for excellence.

10. Are there any famous quotes attributed to Enzo Ferrari? Yes, one of Enzo Ferrari’s most famous quotes is, “The client is not always right.” This reflects his commitment to the purity and performance of Ferrari cars, sometimes prioritizing engineering excellence over customer demands. Another well-known quote is, “I would like to be remembered as a man who has done his best in his own time.”